|

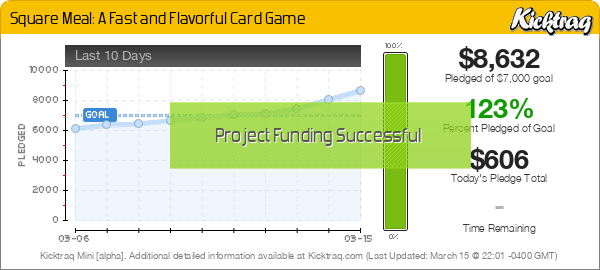

| Image from www.analoggames.com. |

This is the fourth article in my series for new game

designers. In previous articles I’ve discussed the use of

rules,

time, and

math

in games, and how to avoid common pitfalls. In this installment, I will address

the actual, physical space your game fills. In the age of Gloomhaven, Ogre, and

other massive Kickstarter-fueled beasts, you might need to give some sober

thought to the size of your game.

Observation #4—Shelves are Small

The now commonplace “game shelfie” gives players an

opportunity to show off their vast collections. This might give one the

impression that storage space for games is vast and limitless. However, this is

far from the truth. For every hobbyist with a dedicated game room lined with

hundreds of games, there are many other gamers of more modest means. And even

these alpha-gamers face the cold reality of running out of space. The periodic

game purge has become as ubiquitous as the shelfie.

The situation for individual gamers represents only the

tip of the iceberg. Bright, colorful store shelves in game and big box stores

present a cheerful front but disguise a cut-throat struggle for the attention

of shoppers. Every inch of space must fight tooth and nail to earn its exalted

place before the eyes of consumers. Games that don’t sell are quickly shifted

to the bargain bin. And we have yet to mention the rows and rows of crates in

distributor warehouses across the world. With a thousand new games flooding the

market every year, finding a place on a shelf can be a real and ever-increasing

challenge.

So what has all this got to do with designers? The bottom

line is that, generally speaking, your game needs to be as small as possible,

while still delivering your core experience. This is not to say you can’t make

a solid table-hog miniatures game in a boat-sized box. However, each and every

last component must pull its weight. Publishers, and ultimately, gamers, want

to get the best bang for their buck. Do everything you can to reduce the

production cost of your game while providing good value and matching the

expectations of players.

The best way to get a sense of this is by looking

carefully at published games. While games can come in nearly any shape

and size, the industry has a few standards. A tuck box card game (Uno) will

retail for around $10. This is expected to be fairly simple and last around

15-30 minutes. A more expansive card game (Exploding Kittens) will come in a

small two-piece box and sell for $20. This size game may only have cards, but

can also include a few small components. Players are still expecting a light,

quick experience. Next we have a slightly larger box (For Sale) selling for

$25-30. Now players are expecting a game that can last up to 45 minutes. This

brings us to the most popular board game size, the 12”x12” square box (Ticket

to Ride) retailing for $50-60 ($70 if there are extra components and the game

is longer). Players now want to see a board (or large shared play space), a

fair amount of additional components besides cards, and a play time of 45-60

minutes (or a bit more). Finally, we come to bigger boxes (Scythe, Eclipse,

Thunderstone Quest, Gloomhaven). We expect these games to cost $70-100 (the

price will go down if the game becomes popular enough to print in high

quantities). Often the “all-in” pledge on Kickstarter for these games will be

as high as $200-300 or more. Players expect many hours of content and session

times of 90-120 minutes or more. They will also accept longer rule books and

more convoluted mechanisms in games of this size.

As you can see, there is a pretty close relationship

between the size of a game, its complexity, its play time, and its cost.

Designers would do well to stay within these bounds. Much like a wrestler might

need to shed a few pounds to qualify for a lower class, a game often needs to

be more condensed to hit the right note in the marketplace.

It has taken me a while to learn this lesson. I once

designed a game with loads of cardboard hex-shaped tiles where players were

building and exploring a map in real time. The game would have needed a large

square box and a retail price of $50. The problem was that the game only lasted

about 15 minutes. While the game was fun, it was simply too big for the

experience it offered. Regrettably (and stubbornly), I repeated this mistake

with another real time train game a few years later.

How can you decrease the size and component count of your

game? Here are a few ideas:

First, consider the parts of your game that are not used

as much. Maybe there are special tiles that only come into play during certain

times. These might need to be shrunk or eliminated. Often, the solution is to

combine the component with another part of the game. While you don’t want your

players to run out of a component such as cubes, many of those cubes will not

often come into play. Think about ways to alter the rules to allow a reduction

in the total number of cubes needed.

Second, think about the scoring system. One common

solution is to replace money or tokens with a scoring track (often found around

the edge of the board). Some games solve this problem by using a dials built

into the player boards or the board itself (although this can also be

expensive). This method can also be used to track other stats in the

game—health, damage, morale, resources, etc.

Finally, cards are cheap. Wooden, plastic, and metal

components look sharp, but they can add considerable expense (as can dice).

Figure out ways to use more cards and fewer of the other types. Cardboard is

also relatively inexpensive, but it can sometimes add too much weight or

command a larger box size to accommodate too many punch boards. Cards magically

provide loads of design space for a fraction of the cost.

One final caveat: while it is vital to keep your

components to a minimum, you might want to keep an eye on table presence. A

game needs to look impressive and interesting once it’s set up on the table. It

needs to grab the attention of people walking by. The “toy factor” of a game

can be an important selling-point. In this case, extra material used in an

innovative way can pay dividends in a memorable player experience. Sometimes

more is more, if you do it thoughtfully.

I hope this has been helpful. It takes real creativity to

condense a prototype into a smaller and smaller size. The more you can do to

reduce the production cost for your game, the more attractive it becomes to

publishers and the more value players will enjoy. Thanks for checking out this series of articles. I may think of others from time to time, but this will conclude the series for now.